Protecting Native Bees

/Native bees sealed into bamboo sticks in a native bee house. (Photo by Charlotte Ekker Wiggins)

Protecting Native Bees

Adding native bee houses to your garden is a wonderful way to add nesting spots for those solitary native bees, of which the US has about 4,000 out of the 20,000 native bees worldwide. However, most native bee houses are sold without a protective metal covering keeping birds from using the native bee houses as snacking stations.

To protect my native bee houses, I add small gauge wire around the front to keep birds from eating the bees while they hibernate in their mud-covered homes.

Several bees have settled into this native bee house in my garden. (Photo by Charlotte Ekker Wiggins)

To add wire around your native bee houses, slowly cut the wire with wire cutters the length of the front of the native bee house and wider on the sides.

You also want about an inch in the front between the native bee house and the wire.

I fold, then nail one side of the wire, adjust the distance on the front, before finishing the other side. (Photo by Charlotte Ekker Wiggins)

For native bee houses with angles, just fold the wire to fit being careful not to cut or nick your fingers.

Fold wire to fit around angled corners before nailing in place. (Photo by Charlotte Ekker Wiggins)

Keep measuring as you nail to make sure you don’t pull the wire too tight and close to the native bee house. The idea is to keep birds from getting their beaks into the native bee nests.

Leave about an inch space at the bottom between native bee house and wire. (Photo by Charlotte Ekker Wiggins)

Take it slow so you don’t puncture your hands with the cut wire.

Two more native bee houses ready to go outside. (Photo by Charlotte Ekker Wiggins)

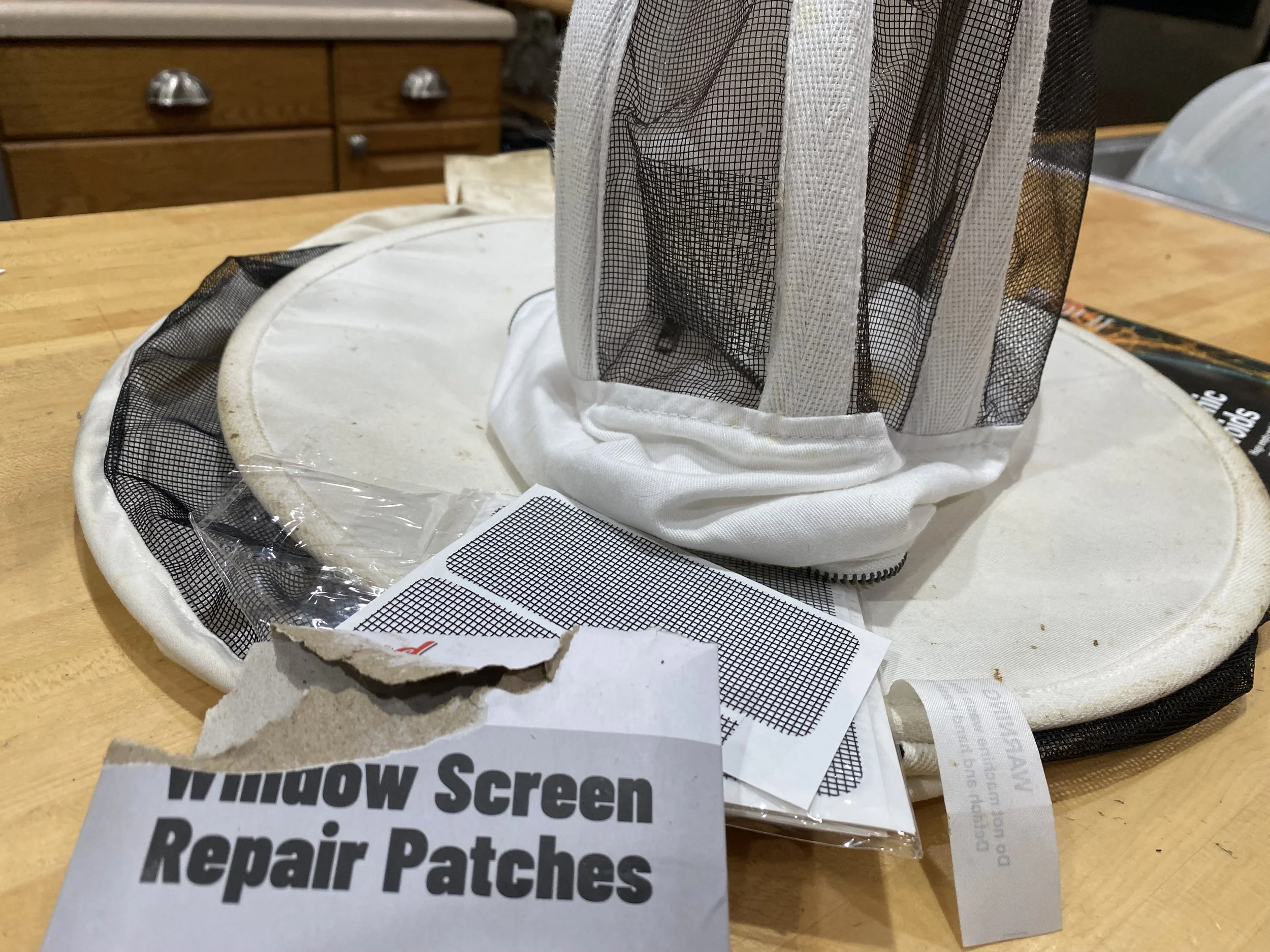

Not all native bee houses are so large, my first native bee house has been repaired several times but still hosts native been tenants every year. The key is to protect the slumbering native bees from birds.

My first native bee house, a little worse for wear but still hosting tenants. (Photo by Charlotte Ekker Wiggins)

There are a number of sources you can tap for native bee houses, from Aldis to your local home and garden centers.

If you are handy, you can also dry bamboo and cut the stems into same length segments and make a box to house them.

Either way, having native bee houses in your garden will encourage wonderful pollinators!

Charlotte