How to Learn Beekeeping

/learning to “read a frame” of bees is a critical beekeeping skill. here I’m checking that bees are taking care of brood cut out of a wall. (Margaret Ronzio photo)

How to Learn Beekeeping

Keeping honey bees is a fascinating, rewarding and yes, sometimes frustrating hobby. Here’s a step-by-step guide to help you get started:

1. Research and Education

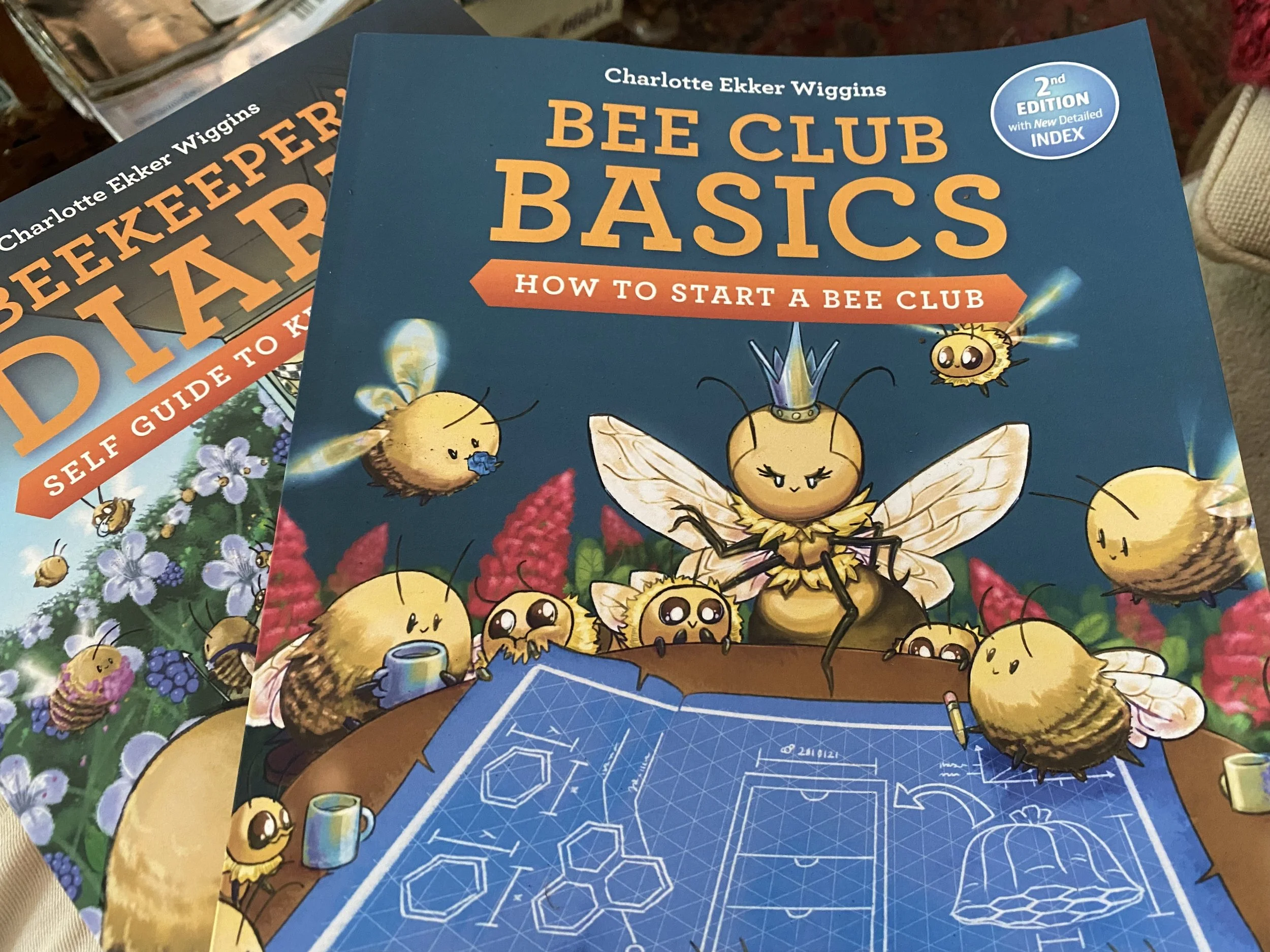

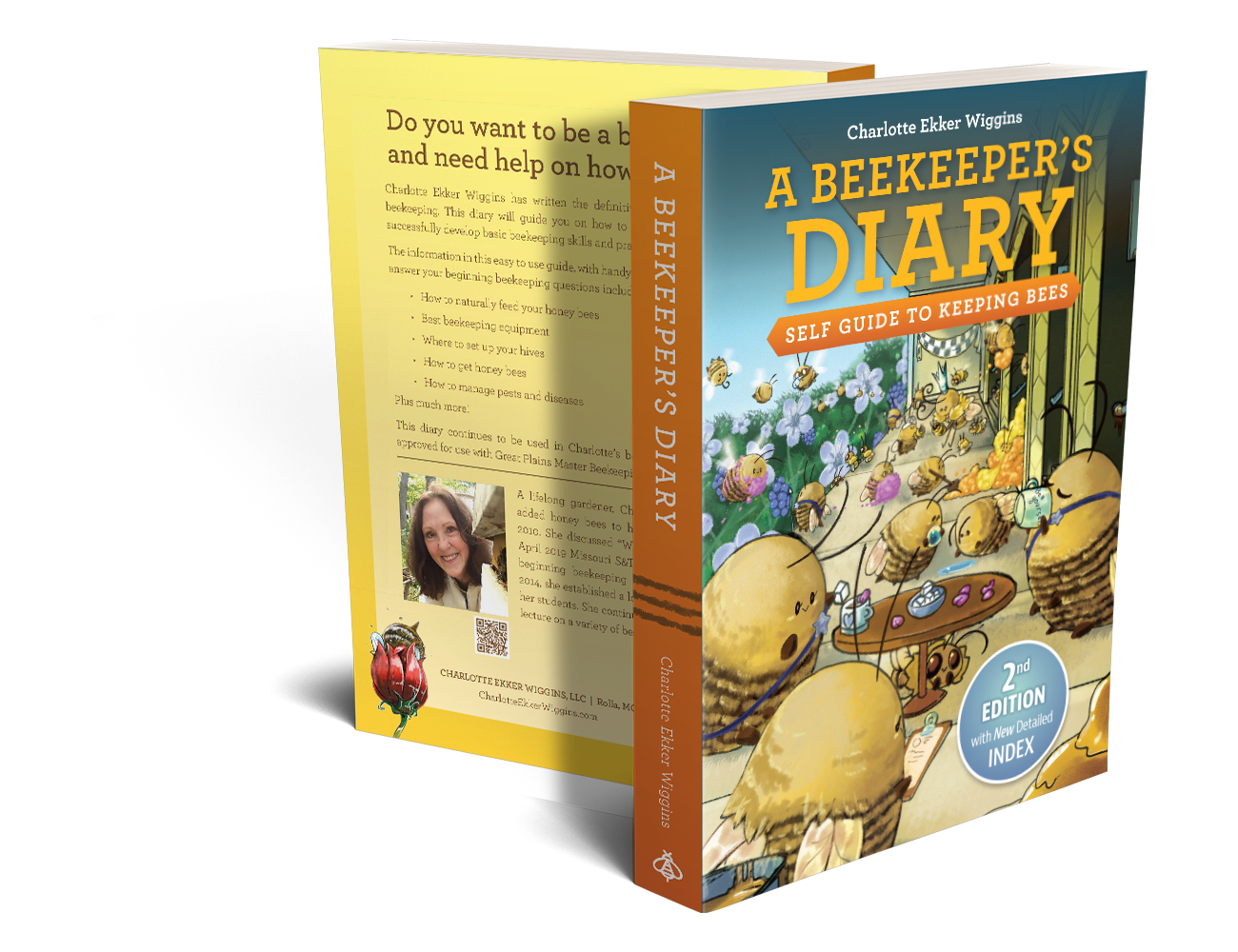

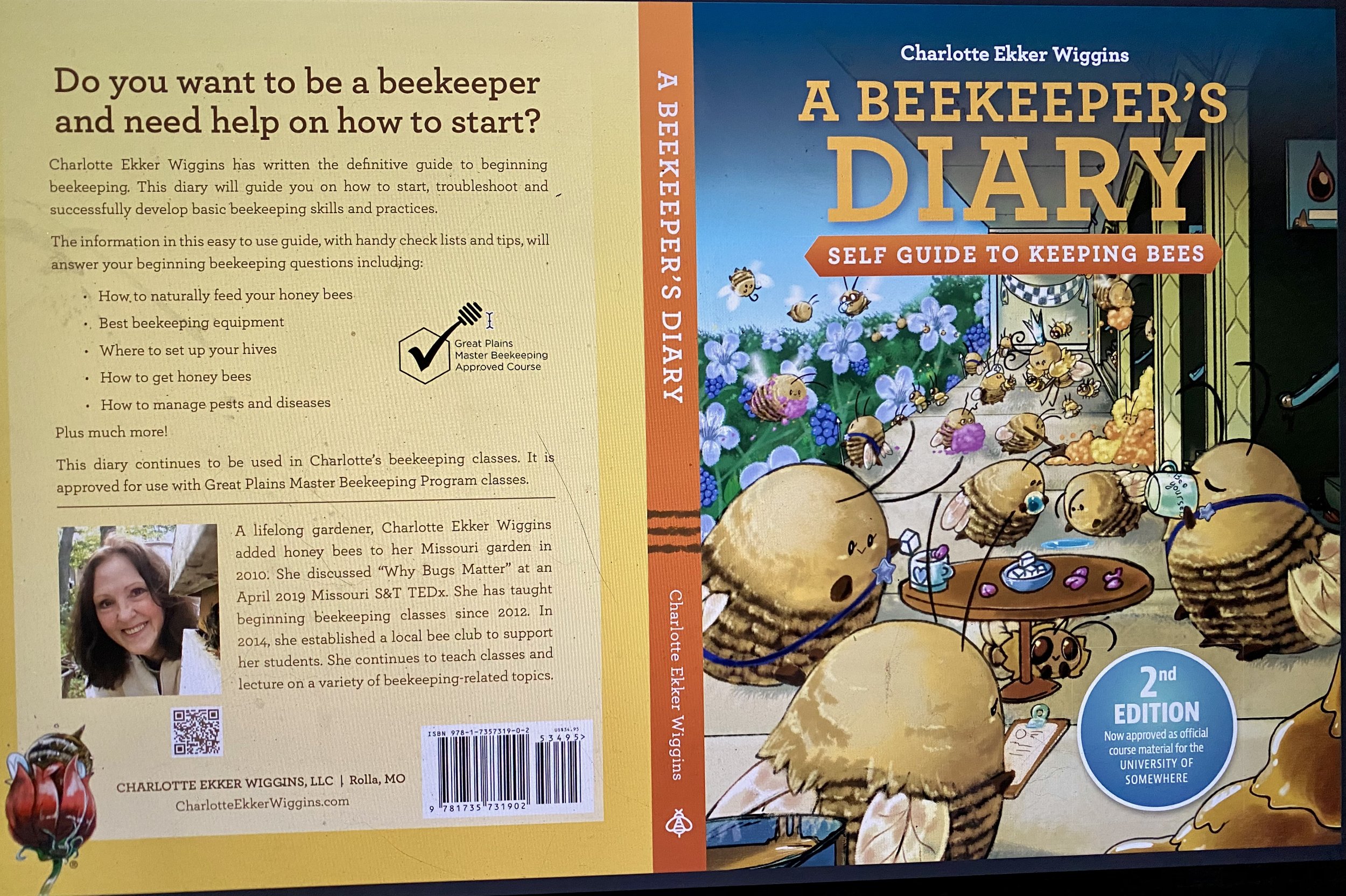

Learn the basics of beekeeping by attending local beekeeping courses, joining a beekeeping club and reading books. “A Beekeeper’s Diary, Self Guide to Keeping Bees” is an excellent guide to introduce and guide you.

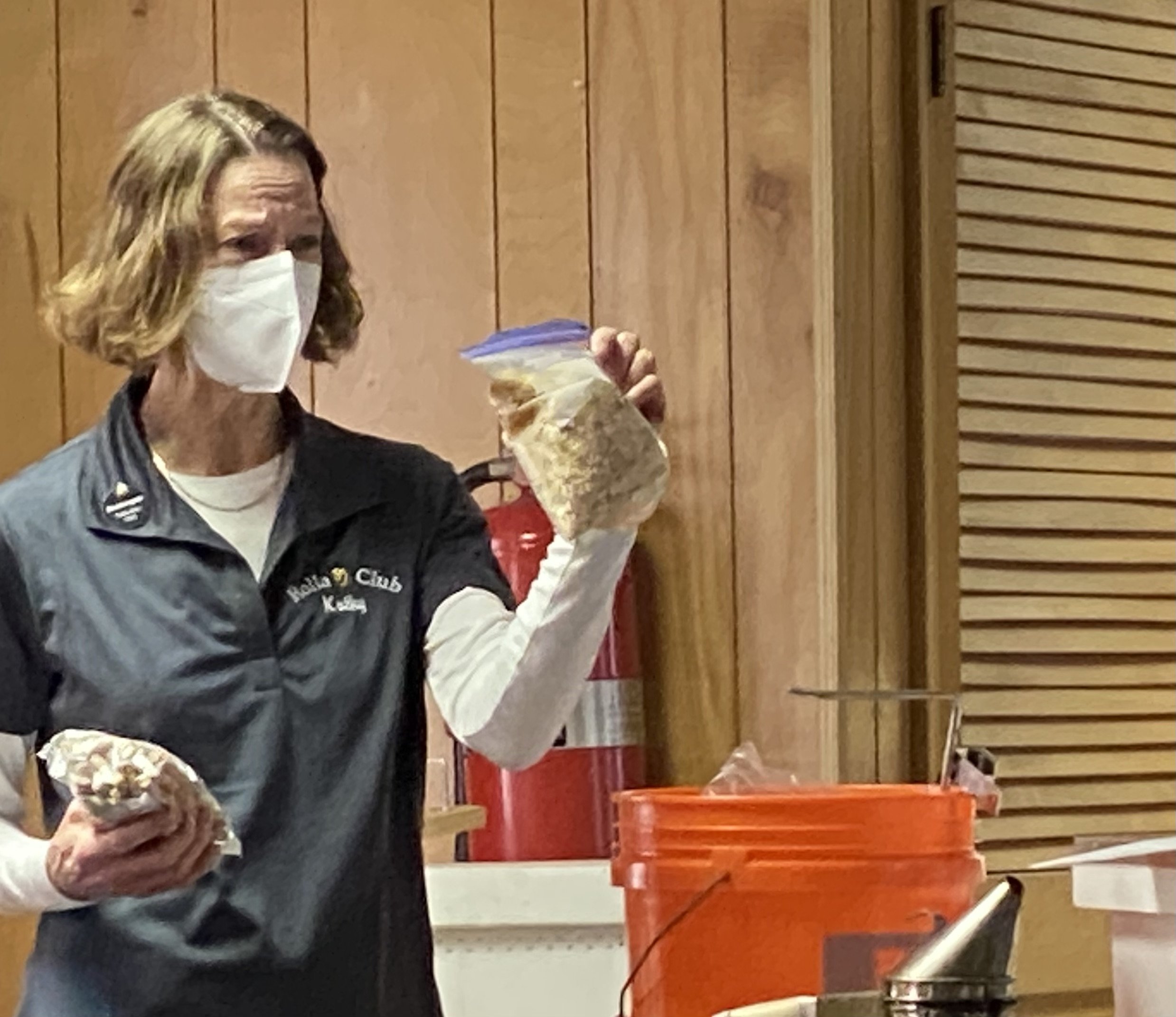

The key is to understand bee biology, hive dynamics, and the seasonal cycle of beekeeping. Attending a local club and an open teaching apiary where you can see bees working is also helpful.

Bees are living creatures with their own objectives and schedules. As beginning beekeepers, our biggest challenge is to stay out of their way and learn from them, not dictate to them.

2. Check Local Regulations

Research local laws and zoning regulations about keeping bees in your area.

Obtain any required permits or licenses for backyard beekeeping.

3. Choose the Right Location

Select a sunny spot with wind protection, away from high foot traffic areas.

Ensure the site is close to flowering plants and has a water source nearby.

Position the hive entrance away from pathways or neighbors to reduce disturbances.

4. Acquire Equipment

Purchase essential beekeeping tools:

Bee suit or jacket with a veil for protection.

Gloves (optional but recommended for beginners).

Hive tool for managing frames.

Smoker to calm bees.

Choose a hive type. Langstroth is the best one to start with because parts are easily available and most beekeepers used this hive in their own operation.

5. Select and Install Bees

Decide on the type of bees (e.g., Italian, Carniolan, or Russian) based on your local climate and management style. Ask established beekeepers in your area for recommendations.

Obtain a nucleus colony (nuc), a package of bees with a queen, or a full hive from a reputable supplier. Ask club members what they recommend for your area.

Install the bees in the hive during early summer when flowers are abundant.

6. Provide Food and Water

Offer a sugar syrup solution if natural forage is scarce, especially when starting.

Ensure a nearby water source for bees to land on.

7. Perform Regular Inspections

Inspect your hive every 7–10 days during the active season to:

Check for brood (eggs, larvae, and pupae).

Ensure the queen is laying eggs.

Monitor for pests like Varroa mites or diseases.

Assess the colony’s food stores and comb building progress.

8. Manage Pests and Diseases

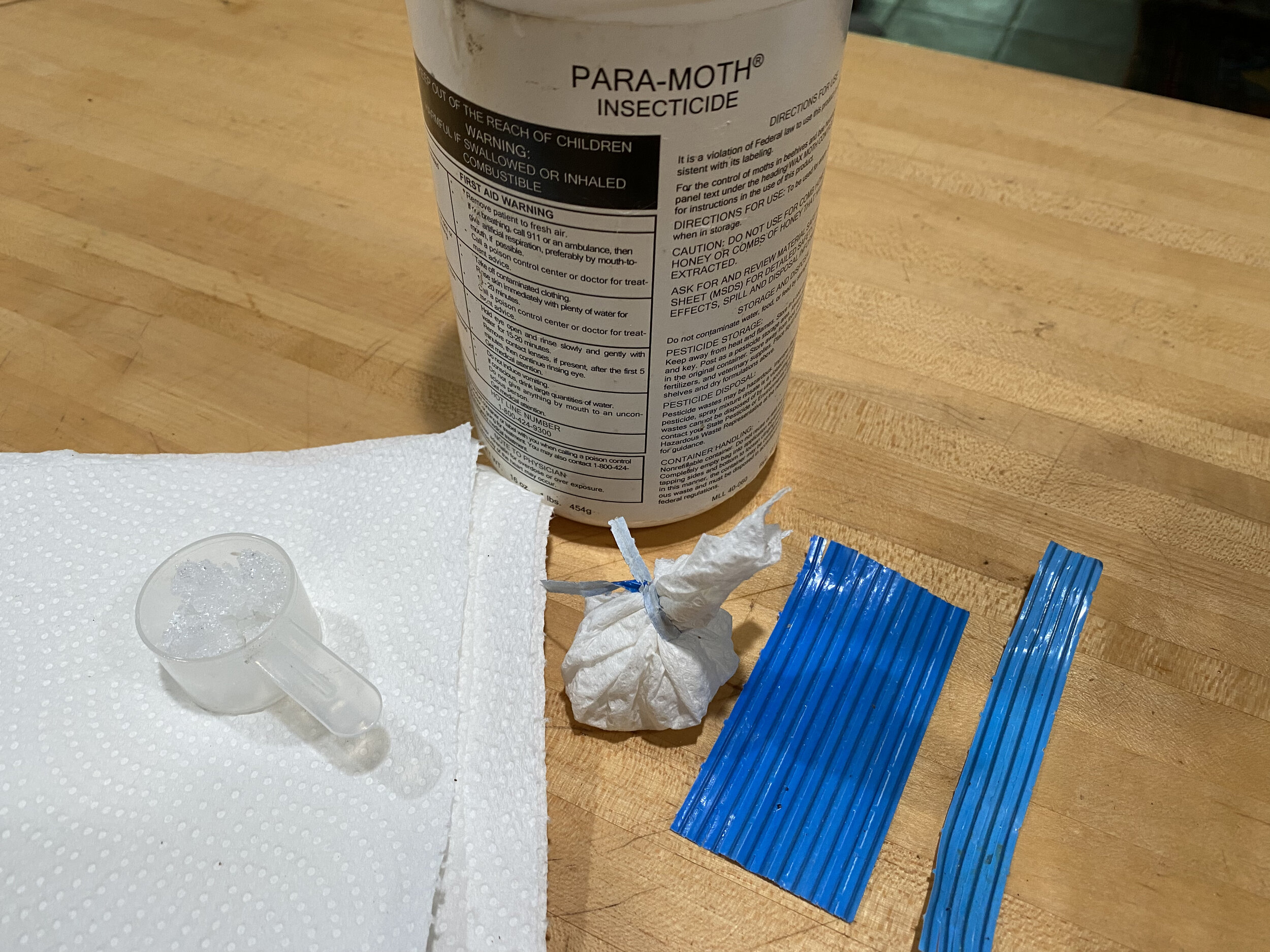

Learn to identify common bee pests and diseases.

Use integrated pest management (IPM) techniques to maintain a healthy hive.

Replace or treat infected frames or hives as needed.

9. Harvest Honey Responsibly

Wait until the hive is well-established, typically after the first year, before harvesting honey.

Only take surplus honey, leaving enough for the bees to overwinter.

10. Prepare for Winter

Ensure the hive has enough food stores (usually 60–80 pounds of honey for winter survival, depending on climate).

Use insulation or wraps if needed for your region. Reduce hive entrances.

Check on the hive occasionally during winter but avoid disturbing the cluster.

Conclusion

Most answers to beekeeping questions begin with “it depends.” No two years of beekeeping are ever the same, either, so this will be continually challenging as you adjust to other factors you have no control over; weather, what plants are blooming, and what your bees are doing.

Still with me?

Great, then welcome to the wild world of backyard beekeeping!

For more beekeeping, gardening, cooking and easy home decor tips, subscribe to Garden Notes my weekly free newsletter.