Catching Swarms

/A little worker bee takes a break from flying around scouting new bee home locations. (Photo by Tom Miller)

Catching Swarms

Every spring, beekeepers you may know will get just a little giddy at the mention of “swarms.” While members of the general public conjure up some low budget Hollywood disaster movie at even the thought, to a beekeeper a swarm is everything from “free bees” to an invitation to an adventure.

First, honeybees swarming are not something to be feared. In most cases, bees in a swarm are at their most docile. Full of honey before they left their last home, these bees are waiting for scout bees to locate new possible houses while they literally hang out – on your fence, the side of a house, maybe a nearby tree. The scouts return to the bunch of bees, describe the potential home and the bees “vote” on which one they like best. Once the consensus is reached, the swarm will leave their spot and follow the scout bee to their chosen location.

Swarms have a very short life span, 3 to 5 days so if you see a swarm, please don’t spray it or swat at it, visit rollabeeclub.com for a list of area beekeepers who will come out to catch the swarm.

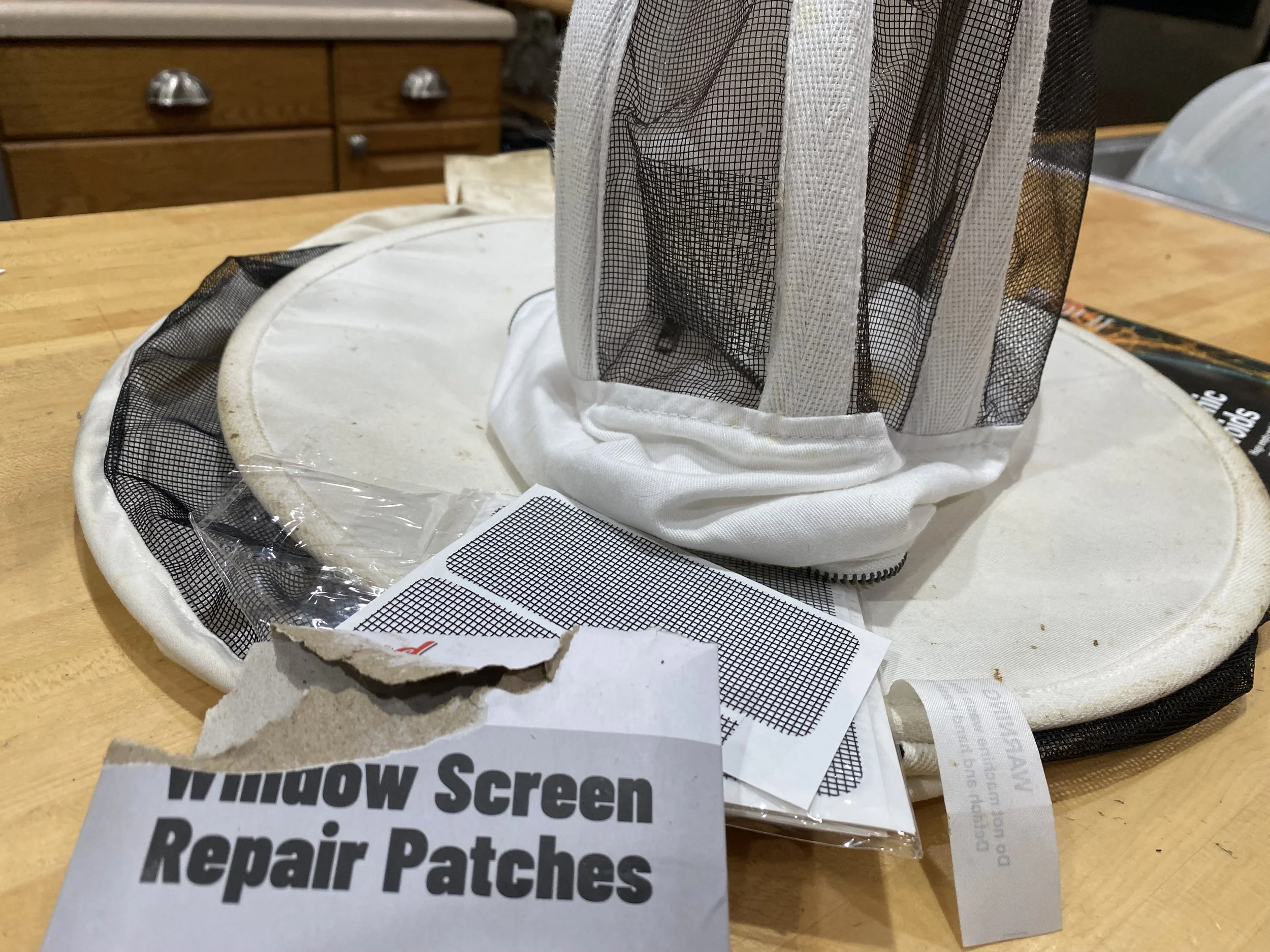

To go after swarms, beekeepers are like first responders, vehicles packed with extra bee suits, possible helpful equipment like a ladder and empty hives in various sizes.

If one is lucky, a beekeeper can entice a colony into a new home with ample space, hive frames already with places for the queen to lay and maybe a whiff of honey. To say that swarms are “free bees,” however, dismisses the work associated with catching a swarm.

To be successful in keeping a swarm in a hive, a beekeeper has to feed the colony sugar syrup, simulating nectar bees find in flowers in nature. In more than half the swarms caught, the queen also has to be replaced since most queens are old and past their prime in terms of laying eggs.

Even with good care, the national figures indicate 40% of all caught swarms make it through their first winter so in spite of all of the work, there still is a good chance the bees won’t make it.

Some beekeepers are also unaware that varroa mites travel on bees and small hive beetles travel with bee swarms, continuing to cohabitate with bees once they settle in their new accommodations. Stressed bees generate a pheromone that triggers the ladybug-size, black sub-Sahara African small hive beetles to go on an egg-laying spree, each female bug laying up to 1,200 eggs a day. At that rate, these imported bugs can easily take over a bee colony in less than a week.

Muslin kitchen towels are very helpful in swarm-catching, they help show what bees are doing. (Photo by Charlotte Ekker Wiggins)

In spite of the challenges, catching swarms are a lot of fun, especially those from one’s own hives. The secret is to find the queen and get her inside the new possible home. Once the queen is inside, the rest of the bees will quickly follow her inside. All the beekeeper has to do at that point is wait until dark, close up the hive and move it to its final destination.

Charlotte